Authored By: Jonathan Spence

Data and the internet are becoming ever more critical to the planet’s residents. Even the smallest rural villages in Kenya or India are likely using data services on a daily basis; services whose importance can often be placed far ahead of electricity or even sanitation. The rise of the likes of M-Pesa in what many in the developed world would (arrogantly) consider backwaters is testament to the power of communications and information to transform the lives of all.

No matter whether its an SMS message, financial transaction, email, complex business process or cat video, almost all that we do online will have data being processed at or at least being routed through a datacentre. For those who haven’t visited, datacentres are typically quite boring places, loud with the sound of thousands of small spinning fans and industrial air conditioners. Through my early days in the IT field I used to spend inordinate amounts of time in them installing or configuring equipment, I was always glad to leave, usually at 3am.

Datacentres are not built as places for humans, in fact it would be much better if humans needn’t venture into them – bring on the robotic server technicians to replace parts and plug cables!

One thing a lot of people don’t realise about datacentres is that they use MASSIVE amounts of electricity to run. While the trend for the likes of home PCs and mobile devices has been to downsize and reduce power, datacentres have been the opposite. The servers which sit within are becoming ever more dense and power hungry.

Let’s start with a quick bootcamp. I do understand if this paragraph is TLDR… about how virtually every datacentre is structured. Firstly the datacentre will have a room(s) or hall(s) containing racks into which the equipment like servers actually go. These rooms and halls will usually be relatively sealed for airflow and have high security access such as fingerprint readers, swipe cards etc. A standard datacentre rack is 19” wide (~50cm) and it varies but usually about ~1.2m deep. All equipment such as servers, switches, routers etc. Must be the ~50cm width to mount but the length can vary. The rack are broken up into RUs or “rack units” on the vertical plane of about 4.5cm per RU. A piece of equipment such as a server is measured in RUs and this is how much vertical space it takes up in a rack. Usually a server would be 1RU or 2RU but some big pieces of equipment can be 10RU or more. A rack would be usually between 42-48RU high. So if you had 1RU servers, you could fit 48 into a single rack.

A standard server rack. Check the red circles to see how the vertical height system works [3]

A standard server rack. Check the red circles to see how the vertical height system works [3]

OK now you are a datacentre expert, let me explain about what has been happening in the industry. Datacentre space is not cheap, your 1.2m x 0.5m x 1.9m space (yes that is ~1m³) may set you back $700 USD per month without the other mainstays of the datacentre, internet access and electricity even being considered. Wow it’s quite a bit of money compared to your average 1m² of office space! Alongside this equipment is now more interconnected than ever and there has been a strong push for better utilisation of servers. Previously you had a “server box” running your email, a “server box” running your website etc., what you would find is that each was using 5% of its resources so a big chunk of your RU space was being used by mostly idle equipment drawing not too much power.

Virtualisation through the likes of VMware has come along and encouraged the consolidation of these “workloads” as the industry likes to call your website, email etc. Onto less servers with higher utilisation. And now, while you are definitely saving overheads in power use over all the boxes, you have a tighter area using more power than it once did. This has encouraged others to more densely pack their servers and datacentre space to get the best “bang for buck” on both equipment and space.

Skyrocketing Power Usage

To skip a few steps and reach the point, whereas ye-olde 2000s rack may have been using 5KW of power for all the equipment inside, many racks these days may be using 30, 40 even 50+KW of power. With the birth of the age of AI (artificial intelligence) and huge data processing, with specialised equipment that is coming out, this could get even higher. Imagine 50 fan heaters stacked in 1m² of your house and you can get an appreciation of the power used and heat generated. In fact the heat is a big problem, it can take just as much air conditioning power to reduce the heat so it doesn’t cook the equipment or the poor old datacentre workers.

Now most datacentres I have worked in were relatively small – maybe 100 racks each; I did a quick web search and in 2012 AWS – Amazon Web Services (AWS) had ~5000 racks in one of their hosting regions in the USA. There’s a recent report from Greenpeace that the AWS region may have 1 Giggawatt (GW) of power at that site very soon and while they won’t be at capacity, they will reach there as they expand – with technology growth a certainty I would claim.

So what does 1GW look like? According to the Australian Energy Regulator, the average daily power consumption for a 3 person house is 19.2kWh. While there will be spikes in the morning and evening, if you flatten this out that is 0.79 kW on average. A gigawatt is 1,000,000 kW. So AWS in a single hosting region in the USA has the capacity and will soon be using the power of ~1.2 million average 3 person Australian homes. That is not a small number.

So how do we power datacentres?

Datacentres will almost certainly draw their power from the electricity grid. Grid operators will have specialised lines at high voltage coming into private transformers for the datacentre. Most will have batteries and power generators to keep everything operating even if the grid loses power. Actually unless you are at Amazon scale where you can probably build your own power grid and power generation, a key consideration of where datacentres are built is how easy is it to get enough power from the grid!

And this flows through to the point of this article, location, location, location.

Just some of the power infrastructure for one of Google’s Datacentre’s in Oregon. [4]

Just some of the power infrastructure for one of Google’s Datacentre’s in Oregon. [4]

One other thing that datacentres are known for is that they are a hub for connectivity, be it internet, phone, private business network or the like, datacentres will have fibre optic cables coming in from all directions; and they are usually the easiest place to get super fast internet connectivity. In fact, before we had UFB (ultra fast broadband – New Zealand’s highly successful version of the Australian less-than-successful “high-speed” NBN broadband network), the main reason I started using datacentres was actually more driven by the fact they had fast internet connectivity rather than security or reliability features in the early days.

The nature of communications and the internet means that a datacentre could literally be on the other side of the planet. The internet has enabled us, no matter where we are to ubiquitously use any service (well any is not always the case – apart from perhaps those countries with censorship of which the list is unfortunately ever growing). That being said, we usually want a datacentre close by as the cost for our ISP of getting the data to somewhere close is much less. Also the latency, the physical time it takes for lights to pulse down the fibre optics, really has a noticeable effect on speed – a closer datacentre means lower latency and greater speed. If you want to know more, ask an online gamer, financial trader or someone trying to run a Citrix session to another continent.

Why New Zealand should be Australia’s datacentre hub to help save the planet

So far we have figured out that datacentres use a heap of power and that is growing and that their location doesn’t really matter thanks to the internet (as long as we have low latency and low bandwidth charges). Let’s go through some other points framing this idea:

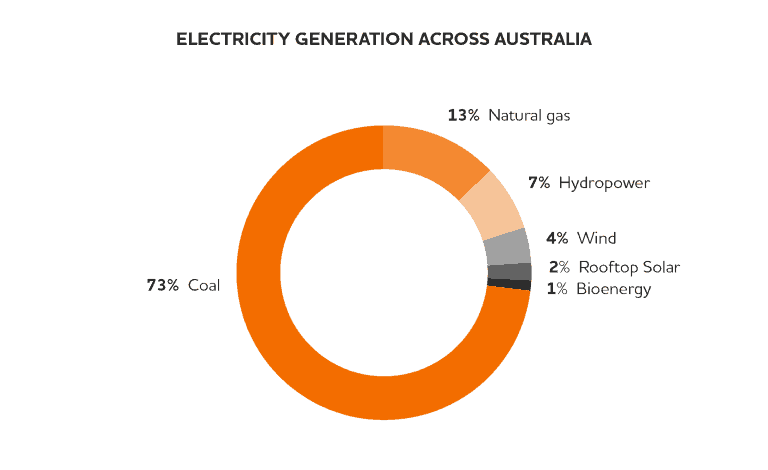

- Global warming, the increase of the Earth’s temperatures as primarily induced through humans’ release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. It’s something most want to protect the planet from for the benefit of future generations (or even current generations with existing predictions!). One thing that drastically separates Australia and New Zealand’s power grids is the source of generation. While virtually all of Australia’s power is generated through means which produce a heap of CO₂ such as the burning of coal, almost all of New Zealand’s electricity is generated through no or ultra low CO₂ emission sources – namely hydro electricity and geothermal power. Australia has little hope in catching up to New Zealand in the use of “renewables” to generate power.

- Another unique situation is the large role that a borderline economically unstable aluminium smelter plays in the consumption of the total generation in New Zealand. It meanders along on government subsidies but these can only go so far. The final closure of this facility would create a massive glut of power generation sitting idle waiting to be tapped and depress power prices. There is a flurry of new undersea fibre cables are being brought online linking the countries, the brand new TGA cable supplementing the existing Southern Cross Cable and the new Hawaikii cable linking the countries is about to come online too. This means lower bandwidth costs (most probably cheaper than within Australia itself) and considerable redundancy.

- At ~3000km latency between East Coast Australia and New Zealand is ~30ms ie. 30 thousands of a second for data to go from Australia, to New Zealand and arrive back to Australia again – that is faster than Sydney to Perth or about 1/5th of the time between Australia and the USA. It’s completely acceptable for virtually every application including those demanding online gamers.

- New Zealand is much cooler than Australia, especially in the South – this means far less power is needed to cool the equipment in the datacenter – a big concern when 1m² is pushing out 50KW!

It all just comes together. In fact on the last point, the aluminium smelter is in one of the coldest parts of the country and has a massive transmission system to feed it already from carbon free hydro generation. It has to be one of the best set of circumstances begging for those wanting to build an eco-friendly and low cost datacentre.

I know others have spoken about this previously. Lance Wiggs wrote a blog about this 4.5 years ago:

https://lancewiggs.com/2013/04/03/can-we-replace-the-tiwai-smelter-with-a-data-center/

Technology is evolving at massive speed. Take the quoted global power usage of Google in Lance’s article of of 260 Megawatts (MW) – that is now a quarter of a single AWS region. Or the single cable system which has turned into 3 within 4.5 years since he wrote the article. And of course with the ever growing demand to reduce global warming – it’s seriously worth consideration.

Lake (and hydroplant) Manapouri – one of New Zealand’s largest power stations and beautiful lakes. [5] [6]

Lake (and hydroplant) Manapouri – one of New Zealand’s largest power stations and beautiful lakes. [5] [6]

Legal Considerations

One place this may hit some roadblocks is on the legal front. While the techie inside me is always considering the most efficient solution I am cognisant of potential legal issues. More and more countries are mandating their industries keep data “in-border” after a series of international data scandals and fear. To me Australia and New Zealand feel in some ways like a contiguous country – visa free travel, incredibly similar cultures (including the Australian vernacular slowly finding its way into New Zealand!), a history of ANZAC, regulations consistent across – the list is huge. While areas such as the New Zealand and Australian privacy acts differ slightly – so much else can be worked through and hopefully dispensation could be made as part of the countries’ unique cooperation and continuities.

Can we make this happen?

I realise I am a single person making this argument but I am not the only one with this thought train. In a recent discussion with a major NZ based crypto-miner (crypto-mining takes a HUGE amount of energy to power the computing equipment also), he also was keen on the idea and was far more progressed with trying to make it a reality. It seems that without an industry and potentially government behind supporting such an initiative it may be difficult to make happen at a large scale.

Actually what kicked things off for me to write this blog was twofold.

Firstly, my AI based data extraction company, Xtracta is a user of AWS and have been servicing a major new key client from AWS in Australia. To me it feels like a backwards step providing a service to this client from hot and global warming inducing Australian hosting compared to the clean power and lower temperatures of New Zealand, but unfortunately there is no AWS in New Zealand. Can that change?

The other is a large opportunity we are working on at the moment. It’s ambitious but would see us processing so many documents we are now determining our required resources in the tonnage of equipment and Megawatts of power that it would use. I am not sure if it’s commonplace for SaaS companies to price projects like this!

This project is actually a really good example where something like spot server instances from the IaaS (hosting) companies like AWS, Google, Microsoft etc. could come into play since the client doesn’t need real-time processing. For those who don’t know spot prices allow you to purchase any spare capacity with a hosting company at much reduced rates with the understanding the price for it fluctuates often minute by minute. I am still determining whether it stacks up better for this project.

Anyway…..

Perhaps this is a concept the New Zealand tech community can start to raise and get some serious backing behind it. While I won’t hold my breath for an Amazon, Google or Microsoft to do this (although it would be great to see) – the datacentre space is an insanely fast growing industry. If we can show good economics coupled with NZ’s clean and green brand I think even alternative hosting or infrastructure providers can make this work. Let’s see.

To participate in the conversation regarding this blog post visit Jonathan’s LinkedIn Post.

73% of Australia Electricity is generated by coal-fired plants [7]

Figure: Australian Generation Breakdown [8]

Figure: Australian Generation Breakdown [8]

Attributions

(1) “Inside a customer Data Suite in Union Station” Author: Global Access Point

(2) “Outdoor view of the dam and power station at Roxburgh, Central Otago, New Zealand. The eight penstocks are clearly visible.” Author: Kelisi (CJMoss). Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

(3) “With TPRI Direct and ARIS machines.” Author: Alexis Lê-Quôc. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic

(4) “Google Data Center, The Dalles” Author: Unspecified. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

(5) “A Few Weeks Ago On The Way To Milford Sound At Lake Manapouri.” Author: Trey Ratcliff. Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

(6) “Photograph was taken from the viewing area at the end of the Manapouri Power Station turbine hall” Author: Chrisbwah Creative CommonsAttribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

(7) Unknown

(8) Origin Energy: https://www.originenergy.com.au/blog/about-energy/energy-in-australia.html